This post originally appeared on Substack as a part of my newsletter, East Meets West.

Gojek (sometimes Go-Jek) is an Indonesian “Super App.”

The company was founded in 2010 as a motorcycle (ojek) ride-hailing call center. They began their transformation into a Super App in 2015 with the launch of their mobile app featuring GoRide, GoSend, and GoMart services.

Today, Gojek offers 20+ services through its mobile app. While the company’s core presence remains in Indonesia, it is also expanding into Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand, and the Philippines.

The company is Indonesia’s first “unicorn” and today is valued at ~$10 billion having most recently raised from Facebook and PayPal.

Gojek was co-founded by Nadiem Makarim, Michaelangelo Moran, and Kevin Aluwi (though it seems as if he joined the company 4 years after founding, around the time of transition from ‘call center’ to ‘super app’).

Nadiem, who served as CEO for most of the company’s life, left Gojek in early 2019 after he was appointed Minister of Education and Culture by Indonesian President, Joko Widodo (more on Gojek’s relationship with the Indonesian government later).

Nadiem grew up in Indonesia and Singapore, before moving to the United States to pursue his undergraduate education in International Relations at Brown University. He then spent 3 years at McKinsey in Indonesia before doing his MBA at Harvard Business School. After Harvard, he returned to Indonesia and while founding Gojek (the call center, not the super app), also spent time as the co-founder of Zalora’s Indonesian branch (a Rocket Internet e-commerce company) and as “Chief Innovation Officer” of Kartuku, a company that ironically Gojek would later acquire in 2017.

He came up with the idea for Gojek while at HBS, reflecting on his childhood in Indonesia and how inefficient the ojek market was in Indonesia.

Gojek has raised $4.5 billion+ across 10 rounds of funding. The company’s first round was raised by Singaporean-based VCs Openspace Ventures and Capikris Foundation, with its next round led by Sequoia Capital and DST Global. Since then, Gojek raised funds from a who’s who of investors including private equity firms, KKR and Warburg Pincus, along with many corporate investors including Google, JD, Tencent, and most recently Facebook and PayPal.

The company was founded in 2010 as a call center in Jakarta so that customers could order ojeks (motorcycle taxis) by phone. Similar to Uber and Lyft, Gojek wanted to make it easier to find a driver and eliminate haggling around pricing.

Wikipedia points out on ojeks that,

“Many ojek drivers either own their vehicles or are buying them on credit, although in some areas, stolen motorcycles are common. The widespread availability of cheap, domestic motorcycles made by Honda, Yamaha, and Suzuki, and even cheaper ones imported from China, as well as credit schemes with which to purchase these, have resulted in the rapid growth of ojek. The ease with which driver’s licenses can be obtained has also been a contributing factor.”

It appears that between the founding of Gojek in 2010 and 2014, no outside capital was raised.

By 2014, the call-center was handling about 200 drivers and was mostly a manual matching process between riders and drivers. At this point, Gojek raised money from a few investors, including Sequoia Capital.

When the app launched in 2015, Gojek had drawn inspiration from Uber and Lyft, but made the deliberate effort to launch with more than just ridesharing. My sense of what was going on in the background was that Gojek’s main competitor in Southeast Asia, Grab (which I’ll cover in my next issue), launched in 2012 in Malaysia and by 2014, was beginning to expand ridesharing into Indonesia. Gojek could not afford to lose their home market and wanted to give users multiple reasons to use their app so they launched with several applications for users whereas, at this point, Grab was only ridesharing. Nadiem did not believe ridesharing alone could create a strong enough network effect for the business so Gojek launched its app with motorbike ridesharing, delivery (Go-Food), and shopping (Go-Send).

By late 2015, Gojek was managing more than 300,000 orders every day.

In the first 14 months of the app being live, they had 100M+ transactions across all the offerings.

They quickly launched additional services including Go-Mart (grocery delivery), Go-Clean (a housekeeping and cleaning service), and Go-Massage (for booking spa treatments anywhere).

By its $550M funding in 2016, the app had been downloaded more than 20 million times (corresponding to about ~7% of the Indonesian population).

In 2017 they made a push into financial services and launched a mobile wallet (Go-Pay) that was viewed as a play to bank Indonesia’s largely unbanked population. They made a string of acquisitions (“offline payments service Kartuku, payment gateway Midtrans and saving and lending firm Mapan”) to get them closer to that ambition.

By 2018, the app had 125 million+ downloads and was doing about 1.1 billion orders per year across all of their offerings.

In May of 2018, Gojek announced their intentions to commit $500 million towards its expansion plans across Southeast Asia. The plan was, to begin with, ridesharing in Vietnam, Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines, and then offer those users other Gojek Super App features. They planned to hire and work with local management teams to lead each of these initiatives. I will touch on the progress and strategy for international expansion later on.

As of October 2019, the company claimed to be processing over 2 billion transactions per year.

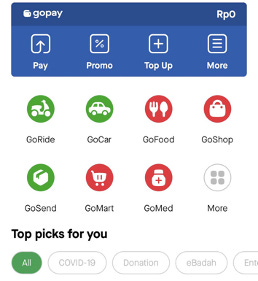

Even though many people know the company first and foremost as a ride-hailing company, getting a ride are just two of about twenty services Gojek has to offer.

When you open the Gojek mobile app, there are several calls to action, but in the top left corner is a focus on their payment features.

When building a SuperApp (one app for many things) that integrates dozens of services you can opt to build services in-house, have third-party APIs where people can build their own apps, or have formal partnerships where you integrate another company’s services into your app. While Gojek does a bit of each, they’ve mostly built services in-house and relied on formal partnerships on the road to SuperAppdom.

Gojek contains many services common to western counterparts like Uber. They have ride-sharing (via car, ojek, taxi, etc.), food delivery, parcel delivery, and moving services.

Some of the more unique services they offer are:

When looking across all of Gojek’s features and services, it’s important to note that

“The biggest moat GOJEK built is payments. Once you’re handling money for a user, you can build a castle of services within it.”[12]

An interesting aspect of Gojek (and other companies in Southeast Asia) is that they have to onboard most of their users on to digital payments. In the early days of Gojek, users paid their drivers with cash. There were no alternatives.

Now, Gojek has a WIDE range of financial service offerings. Long-term when I think about Gojek, they’re much more interesting as a financial services company than as a ride-hailing service.

The core product underlying all of Gojek’s payment offerings is their mobile wallet GoPay, which was introduced in 2015. Like most of Southeast Asia, Indonesia’s population is largely unbanked. One of the onramps for GoPay was that users could top-up their accounts via Gojek drivers. Users could give cash to a Gojek driver who would credit that to their account. Given the ubiquity of their drivers, Gojek became a branchless-bank with their drivers acting as bank branches.

At first, GoPay was just a way to pay for Gojek services, but as of 2018, it began to act as an online and offline digital wallet that consumers could use for Gojek services, non-Gojek online commerce, and offline commerce.

Per a March 2019 Gojek blog post, “GO-PAY accounts for some 30 percent of the total electronic money transactions in Indonesia.” Another post shares that, “GO-PAY is accepted at close to 300,000 online and offline merchants in Indonesia, and processes $6.3 billion of annualized Gross Transaction Value (GTV)”

In addition to GoPay, the company has financial offerings including:

I cut a lot of text from this section, but if you’d like to read 3,000 words going really in-depth on each of Gojek’s product offerings, you can find the text that I cut from this post here.

(Note from Ryan: I am still working on finding the balance of writing thorough yet to-the-point overviews. I don’t want readers to be overwhelmed by the length of the substack posts so I am thinking I will cut a lot from each of these and link out to Google Docs for people who want to go really in-depth on specific sections)

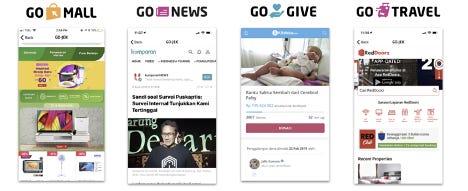

In mid-2018, Gojek launched its third-party platform (“TPP”) so that businesses besides Gojek could build apps on its platform. Their goal was to turn Gojek into the operating system of the phone. WeChat enjoys this luxury in China and Gojek wanted the same relationship with Indonesians and other Southeast Asian citizens. As I mentioned earlier, Gojek, in my estimation, seems to have relied more on developing services in-house than other SuperApps and this was their chance to begin branching out.

The first product they rolled out with the TPP was Gonews (covered here). Since then, they have also rolled out additional products on the TPP including:

● GoGive (with Kitabisa — Indonesia’s largest crowdfunding platform)

● GoMall (with jd.com, “Amazon of China” and an investor in Gojek)

● GoTravel (with tiket.com) to book hotel rooms. Eventually, you will be able to also book train and plane tickets.

● GoSure (with PasarPolis) - Insurance products covered above

● GoEd (with Zenius Education) to offer free online learning

And many more to come…

At a high-level, it seems like right now, Gojek’s third-party platform is still operating in a very closed manner where you get included by entering into a partnership with Gojek. It’s not (yet?) a completely open ecosystem where anyone can add a new application or digital storefront for their small retail business. I imagine this is something that will become more ‘open’ over time. I also understand why in the early days, they want to keep the ecosystem closed (and quality very high).

In the race for Super App domination of SEA, Grab is Gojek’s biggest competitor. Uber was in the race until it sold its Southeast Asia operations to Grab.

Ironically, Gojek’s co-founder and previous CEO and Grab’s co-founder/CEO both attended Harvard Business School at the same time and were friends. (Apparently, they don’t talk much these days)

In the Grab vs. Gojek battle, Gojek feels like the Lyft of Southeast Asia. The fact that Grab acquired Uber’s Southeast Asia operations strengthens that comparison.

Gojek has more services than Grab, but Gojek has not done well to expand outside of their home market, and there’s some debate that they’re no longer even the dominant player in Indonesia. ABI Research says that Grab has 60%+ market share in Indonesia, a figure which Gojek disputes.

In 2017, Gojek’s internal teams, led by their COO decided it was time for the company to begin expanding beyond Indonesia (3 years after Grab began international expansion). Gojek looked for markets with similar characteristics as Indonesia (growing mobile penetration, no food delivery market, and no dominant digital wallet).

In May of 2018, Gojek announced their intentions to commit $500M towards expansion plans across Southeast Asia, specifically Vietnam, Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines. This was announced just two months after Grab acquired Uber’s SEA operations which gave Grab Uber’s operations in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The plan for Gojek was to begin with ridesharing in Vietnam, Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines, and then offer those new users other Gojek Super App features. They planned to hire and work with local management teams to lead each of these initiatives.

Besides just having local teams, each of these new markets would have unique branding (Vietnam: Go-VIET, Thailand: GET, etc.).

As of November 2019, it seems Gojek’s user breakdown was still 80% Indonesia / 20% international, though they hope to get to 50/50 in the next 5 years.

Side note: I visited Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines in 2019 and I used Grab in all of these countries. I think this was because I knew they had merged with Uber’s SEA operations and I trusted Uber, but as a foreign visitor, using Gojek was not even a consideration.

Side-Side Note: If you’d like to dig deeper on where Gojek has struggled with International Expansion, I cut 1,000 words out of this post that you can find here.

One thing that stood out about Gojek (at least as compared to Uber/Lyft) is that they really made an effort to support their drivers and make them feel like they were integral parts of the organization.

“Drivers who could not afford a smartphone were given loans to buy one; assistance was granted to those who didn’t have the necessary paperwork to register legally as a Go-Jek driver. Drivers flaunted their association with the app via branded attire and accessories, which quickly made the streets of Jakarta stream with Go-Jek’s signature shade of green.”Source

Strong political affiliations since the company’s earliest days also appear to have paid dividends. From the start, Gojek seems to have taken a “work with government” approach (again, contrary to USA’s ride-hailing companies).

In Indonesia, Gojek works under the slogan “Karya Anak Bangsa” (made by the children of the nation).

As a result of their approach, they’ve gotten support from people in high places. In December of 2015, Ingasius Jonan, the transportation minister of Indonesia, was rebuked by the President for attempting to ban the use of personal vehicles by Gojek drivers. This was seen as an effort to defend the taxi industry. In response, Nadiem tweeted, “Thanks to President @Jokowi for his support to 200 thousand Go-Jek drivers and 8-million of our application users,”

Then, 7 months later in July of 2016, Indonesia’s President removed Ignasius from his role as transportation minister.

In their marketing language, Gojek (and Go-VIET and GET) make strong nationalist appeals that likely go a long way with government officials. The jackets for each country’s drivers are the color of their flag and have their national flags embroidered.

^Vietnam

^Indonesia

On the page for GoFood, it says, “Do you realize that your order improves the Indonesian economy as well as the Indonesian society? Contributing IDR19 trillion in 2018!”

All companies should talk about their contributions to a country in terms of how many people they employ and (if the impact is big enough) their total contribution to GDP. Per an earlier statistic, Gojek Indonesia employs about 0.75% of the country in some form.

When Nadiem took on his role in the President’s cabinet, he said,

“We’ve created Gojek. An iconic company that flies the flag for the future of Indonesia and Southeast Asia.”

“This company has changed the lives of so many people in Indonesia and around the region, and our key priority is to ensure that we can continue to act as a positive force in society for the foreseeable future.”

In a 2017 blog post, Gojek highlights:

A 2019 report highlighted that Gojek contributed more than $3 billion USD in added value to the Indonesian economy in the prior year and that the average driver earned more than the Indonesian minimum wage.

Gojek also makes it a point in their posts to highlight how much they’ve been able to help small businesses throughout Indonesia. Over 50% of Indonesia’s GDP contribution comes from “micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSME)”. It makes sense that the government would want to support Gojek if so much of what they do is helping this important section of GDP contribution grow.

Through all of Gojek’s offerings, they’re able to help MSMEs with business management and efficiency (Gobiz), financial inclusion (Gopay), market access (Goride) and marketing (Gofood).

Gojek has a program called GO-JEK WIRAUSAHA (“Gojek Entrepreneur”) where they have “trained more than 700 SMEs across Indonesia, to either start a new entrepreneurial business, or scale their existing business. Merchants implementing our business insights experience an average of 71% increase in sales volume.”

I recently read Seeing Like a State by James C. Scott. It is an incredibly dense book. One message I took away was that governments often want to create legibility in communities they govern. They take a top-down approach to try and get communities to adjust themselves to how the central authority wants the world to work. This is done to make governance easier for the central authority.

Gojek embodies the opposite of this in the best way possible. Rather than sitting at HQ and saying “what we did in Indonesia will work in Vietnam” Gojek has taken a boots-on-the-ground approach to growth in new markets.

They hire local leadership teams, promote national colors in each of their regional markets, and get deeply integrated with their merchant partners.

In Vietnam, they say, “Together with the local co-founders of GO-VIET and GET, we believed that it was important to have local brands to reflect the nature of the highly localized app. We believe that these local brands will work best in these markets.” (TBD if this is true or not)

In the home market of Indonesia, Gojek realized early (because of their local knowledge) that competing against taxis would lead to going up against regulators on day one. By the time they started offering car rides a few years into their existence, they already had a chance and did earn the good graces of the government.

The company also recognized how important their drivers were and did many things to make them feel important.

“They held a string of huge, street-fair-style driver recruitment events in basketball stadiums, signing on drivers by the tens of thousands. Drivers who could not afford a smartphone were given loans to buy one; assistance was granted to those who didn’t have the necessary paperwork to register legally as a Go-Jek driver. Drivers flaunted their association with the app via branded attire and accessories, which quickly made the streets of Jakarta stream with Go-Jek’s signature shade of green.”

Gojek is an active investor in and acquirer of other companies. They’ve invested in about 15 companies, many of which they’ve partnered with on different product/service offerings.

They’ve also acquired about 13 companies. Gojek has made most of its acquisitions in two categories. (1) Acquisitions to strengthen their payments offering (2) Acquisitions of Indian dev shops/acquisitions to strengthen their recruiting and engineering pool.

I broke out the section on their acquisitions and investments in a Google Doc here.

After my next two posts on Grab and WeChat, I am going to write a longer post on SuperApps (commonalities, differences, thoughts on how to build one), but for now, I’ll do a brief overview in the context of Gojek.

The best way to think about a SuperApp is that it is the OS of the phone.

Ben Thompson has covered this in the context of WeChat:

“In China the most important layer of the smartphone stack is not the phone’s operating system. Rather, it is WeChat. Or, to put it another way, the operating system of China is WeChat, not iOS/Android”

Besides being able to put “super” in front of your name (which is cool), there are great financial rewards to this. Imagine if every time you opened your phone instead of deciding whether to click on iMessage, Uber, Doordash, Apple News, Chase, YouTube, Netflix, and Booking.com, you only had to click on one app, Gojek, and then within Gojek, you had their “Go” equivalent of all the above choices. That’s a SuperApp.

Each of the applications within a SuperApp also has the potential to make each other stronger. e.g., Because your GoPay is connected to your GoTix, you can buy tickets with 1-click.

Gojek is very heavy-handed on calling themselves a super app. Type superapp.is into your URL search bar and it will take you to a Gojek engineering recruiting website.

So why did Facebook (and PayPal) invest in Gojek?

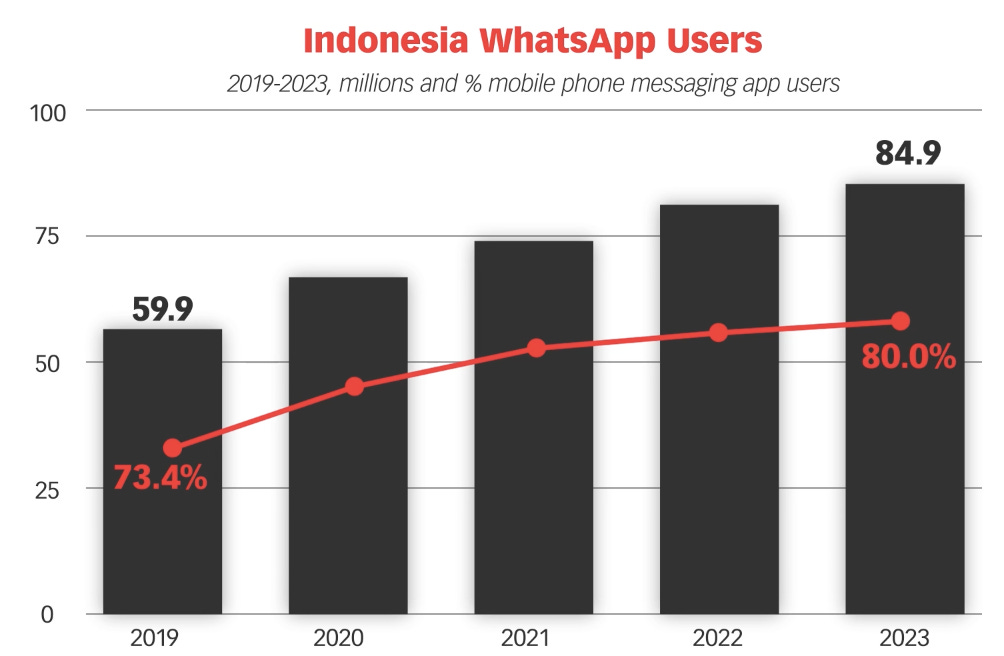

On the Facebook side, this is a chance to further integrate within the Indonesian economy. WhatsApp already has 60M users in Indonesia (~25% of total population) and 75% of the country’s mobile phone messaging app users. Per eMarketer:

In April, Reuters reported that Facebook was preparing to apply for regulatory approval in Indonesia in order to launch a mobile payment service in the country in partnership with a local FinTech firm. At the time, Reuters reported that FB was looking to partner with Gojek, OVO, or LinkAja. I saw one article say that “For Gojek, they will be able to embed Facebook’s digital wallet offering (like WhatsApp Pay) on their platform of lifestyle services across shopping, transport etc.”, but I can’t think of any reason why Gojek would want to invite WhatsApp pay to compete with them in their own app.

A more likely scenario is that, Facebook properties (Facebook.com, Facebook Messenger, Instagram, and WhatsApp) are the only apps in Indonesia that have more users than Gojek. If WhatsApp roles out mini-programs (Mini-programs are little downloadable apps that run inside another larger app. I’ll cover this in my WeChat issue.) and Gojek has an exclusive agreement (aka, no Grab allowed) to build out their product on top of this, it could help to cement their winning position in Indonesia.

It’s worth noting that all PR comments and the FB newsroom post announcing the investment all came from WhatsApp, specifically COO Matt Idema.

As mentioned earlier, Gojek rolled out GoChat in April 2019. It’s possible that that feature is seeing little usage because of WhatsApp’s existing dominance so maybe they decide to kill Gochat, build a Gojek “mini-program” on top of WhatsApp, and ‘The Facebook Company’ decided to not compete with Gojek on payments in Indonesia.

Time will tell…

Given how much money Gojek has raised, it seems like the most likely path they have to an exit is an IPO. They have spoken openly about considering an IPO once their user base hits 50% Indonesia / 50% rest of the world, which given earlier comments, they predict could happen around 2024.

With the recent investment from Facebook, it got me thinking that Gojek could be a key piece of what Facebook needs to turn WhatsApp into a SuperApp (this is a stretch).

Prior to the Facebook investment, there were talks that Softbank (a Grab investor) is pushing for some kind of broad deal between Grab and Gojek, but details were light.

With new leadership at Gojek, there could be an opportunity for an acquisition/merger with Grab, especially given that Grab has picked up more market share in other SEA countries than Gojek has. This would give both companies an opportunity to stop burning cash and really dominate Southeast Asia.

First published on June 21, 2020