Recently, I have been on a mission to shrink my network. When I first made a Facebook (8 years ago in 2010) I went out of my way to friend request any and every distant connection that I came across. I would friend request friends of friends from different towns, people I barely knew, and all sorts of people. Then, it got to a point one day in 2015 where I was looking at my newsfeed and I realized that 70%+ of all the posts I was looking at came from people that I did not care about. It was a bunch of useless B.S. from distant acquaintances. Reading insufferable Facebook posts from friends is bad enough, but reading awful posts from people you barely know is almost a bad as watching Keeping up with the Kardashians. Since making that realization, I got into the great habit of deleting Facebook friends on their birthdays (i.e., if I don’t feel the urge to at the very least wish the person a “Happy Birthday”, I delete them). It’s worked great and I have now shrunk my friend list from over 2,000 to close to 800. This got me thinking about the strength that comes from having small, trusted networks. This runs contrary to many of the best (most highly valued) companies in the world (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Uber, AirBNB) that derive their value from network effects

“[…] in which the value of a service to a user increases as others use it. […] Defensibility may, however, arise through the growth of service that gets more valuable, and more interesting, with each new participant. One nice example of this is Twitter, which is so potentially valuable because put simply, that’s where the Tweets, as well as the personal follower/following relationships, reside. The value of these businesses tends to be composed of the very networks they have created.” Source

My theory is that network effects will continue to be defensible business models moving forward, especially when based on large proprietary datasets, but will begin to lose popularity in environments that are based on person-person engagement.

One of the first cases where I noticed this trend was via the company Casa, “The world’s first open-source home sharing protocol.” You can watch a video detailing their current platform here, but essentially they are building a “trusted network inventory” of homes. You can think of them as Airbnb for friends and family. Rather than going on Airbnb, picking a city, “paying Airbnb to ensure trust”, and then staying at a stranger’s home, I would go on Casa, find a 1st, 2nd, or 3rd, degree connection and then stay at their home, ultimately paying less because I am staying within my network and I do not have to pay for trust (more on the idea of “paying for trust” here) since I am already connected to this person in some degree.

Another area in which I have seen this effect of limited networks play out has been in dating apps. When you think about the evolution of dating apps it went from eharmony and Match.com on desktop → Tinder (2012) → Hinge (2011/2012) → Bumble (2014) → The League (2014). At each step of this evolution, the pool and criteria to pick people from has gotten more and more exclusive and detailed.

In social media, Snapchat has gone out of their way to maintain exclusivity in their platform. Snap’s original product was a non-public messaging platform for a smaller circle of trusted friends. And it is extremely popular especially amongst young Americans (source) that opted not to become members on Facebook (anecdotally, my two little sisters have Snap, Twitter, Instagram, but no Facebook). I think the rise in popularity of FB groups is also evidence of this trend. People want smaller communities, not larger ones. **I would also like to compare the frequency of posting between Snapchat and Instagram stories. (I.e., I know Instagram stories are growing, BUT I would maybe argue that Snap users post more often because Instagram stories are still inherently way more open than Snap stories). **

One of the reasons that Snap flourished was because, as Evan Spiegel has talked about, the product is focused on authentic user content and tried (for as long as it could before going public and having to answer to Wall Street) to keep advertisers and “Influencers” off/limited on the platform.

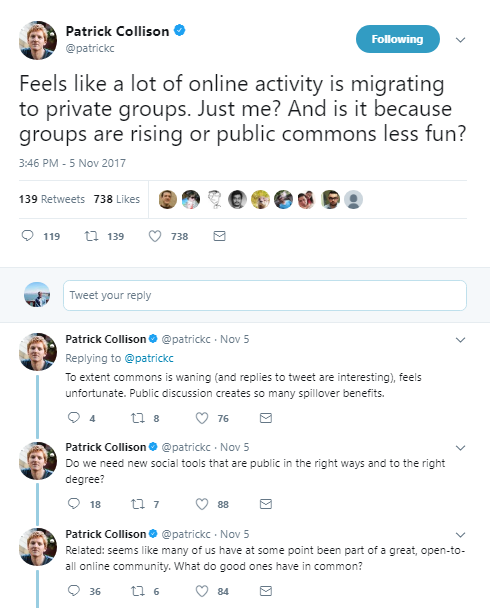

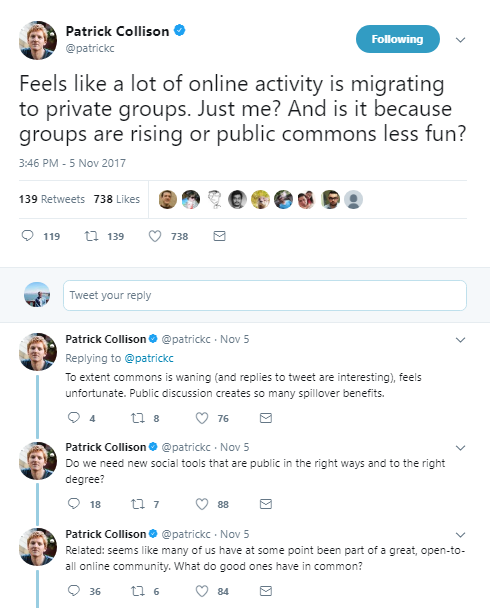

When you first make these social media sites you are excited and want to grow them fast, but now myself and others go and unfriend people. I am going out of my way to shrink my network and create a personal environment. I feel that a lot of people (unless they are trying to become “social media influencers”) follow the same trend. Patrick Collison (CEO, Stripe) noticed a similar trend (image below).

Another example of this idea of limited networks comes from 21.co (now, earn.com). 21.co enables users to email list of subject matter experts 21.co/lists - rather than blasting giant mailing campaigns, paying an agency to survey dozens of households, you can instead survey hundreds of SMEs on topics and receive answers directly from them.

The question that arises as an investor, is what are the underlying causes of this shift? Do people want more privacy? Do people want small niche groups for all their interests? Are people becoming more introverted and in turn, don’t want to interact with the masses?

Additionally, what are the consequences of this change? The one that immediately comes to mind is larger filter bubbles and less experience with diverse views.

First published on November 18, 2017