This post originally appeared in the Bankless newsletter on August 27, 2020 and was co-authored with Baptiste Vauthey. You might also consider subscribing to Bankless, one of the top paid newsletters on Substack.

In July of 2007, the former CEO of Citigroup, Chuck Prince, infamously said this about the subprime lending markets:

“When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing”

Four months later, Chuck would step down due to poor financial performance related to collateralized debt obligation and mortgage-backed security-related losses. Fourteen months later, Lehman would file for bankruptcy, catalyzing the great recession.

It feels impossible given everything that’s happened since June, but it has been just over two months since $COMP went live on June 15 which really kickstarted the current wave of yield farming.

To a degree, it is too early to tell whether or not Yield Farming will drive lasting protocol growth. But, we bet that for most projects, it’s not sustainable.

Yield farming still has many open questions including when rewards dry up or asymptote off: Do customers continue to use the protocol? Or does AUM flow to the next new shiny thing?

There is no shortage of examples of companies paying users to use their product or discounting their product so heavily that users rush to it, only to leave once the incentives dry up.

From a high level, yield farming is a way for a project to incentivize an action by increasing the return or decreasing the cost of the action via subsidies.

In general these subsidies are paid via the project’s native token.

One of the differences between yield farming and previous incentivization schemes is that the incentives from yield farming are not paid with an existing currency (e.g,. ETH, USDT). Instead, DeFi projects can write a few lines of code and issue tens of millions or even billions worth of tokens that the market will hopefully ascribe some value to.

Taking this even further, in many cases, these tokens lack any value capture mechanisms, like using a percentage of fees to buy and burn the token or even pay a dividend. The norm is to release a token with zero intrinsic value and only represents governance rights over the protocol.

So is this the best way to approach this?

Let’s walk through some examples of incentive mechanisms that have been attempted in crypto and then get more granular on DeFi-specific case studies.

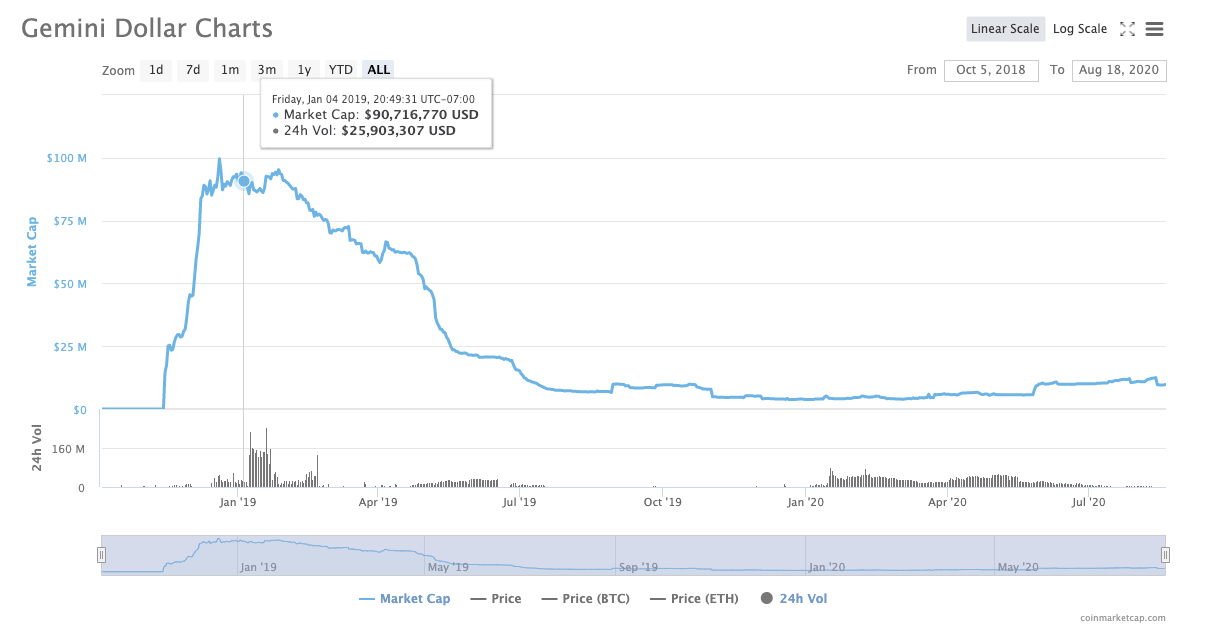

A straightforward example of incentives gone wrong comes from stablecoin issuer Gemini ($GUSD). In January of 2019, as GUSD was near its all-time high, The Block wrote:

To spur adoption, Gemini offered their Gemini dollar to some over-the-counter trading desks at a discount - meaning each $1 token could be bought for less than a dollar. However, traders spotted an arbitrage opportunity in the deal where they could buy the discounted GUSD and then exchange it for Paxos Standard, Paxos’ stable coin, at the full dollar price - pocketing the difference.

As rebates dried up, so did GUSD’s market cap.

GUSD’s death spiral is almost literally a case of what Bill Gurley of Benchmark Capital refers to as selling “$1 for $0.85”. Bill writes:

What if I had a business where I sold dollars for $0.85? What would my revenue growth look like? Obviously, you could grow this business to $ billions in revenue tomorrow. While this may be tongue in cheek, the real-world example of the “dollar for $0.85” metaphor is any business where the value transfer to customers and suppliers and employees cannot be sustained at a positive profit. The customer will be thrilled with any “below market” offering and will rush in to get all they can. In this case, the growth was actually created by the demand for the unsustainable offering.

One way to think about what was happening with GUSD was that people did not want GUSD, but they wanted the incentive that GUSD was offering.

FCoin, founded by Huobi’s former CTO, was once the hottest exchange in crypto. As far as we can tell, they brought the concept of “transaction fee mining” to the crypto ecosystem. Transaction fee mining was like Yield Farming V1 (but way more centralized and scammy).

FCoin distributed 51% of its native tokens (“FT”) to users as a way to reimburse their trading transaction fees. FCoin incentivized users to transact frequently since the platform reimbursed 100% of the transaction fees that users paid with FT tokens. 80% of the exchange’s daily revenue from transaction fees were paid back to users in the form of FT tokens.

In the FT white paper (which belongs in a cryptocurrency history museum) they described this process as:

“Most importantly, FCoin has pioneered the “Trans-Fee mining” model, in which more than half of the platform’s total FTs will be rewarded to the community’s users to offset 100% of their transaction costs. In an unprecedented fashion, the FCoin community will distribute 80% of its revenue to FT holders.”

This trading scheme made FCoin, at one point, the highest volume exchange in crypto.

In practice, what happened with transaction fee mining was that you were participating in an “indirect ICO” (or as Binance Founder CZ called it at the time, a “disguised ICO”).

In a typical ICO, you exchange BTC or ETH for the ICO token, usually at a fixed ratio. With FCoin, you were trading on their exchange, maybe something like the BTC/USDT pair, you paid your fee in USDT, and then received FCoin tokens (“FT”) in return. So you were giving away a token with actual value—USDT—and getting a new, arbitrary token in exchange.

In practice, what caused this scheme to fail was that FCoin was minting new tokens every day to pay out the dividends, in turn increasing supply. While the mania drove an initial price spike, eventually FT crashed because of (oversimplification here) too much supply.

This constant inflation decreased the token value for existing holders, giving holders more of an incentive to sell as soon as they received the FT dividend.

Encouraging an active community via voting rights isn’t anything new. MKR has been doing this since late 2017.

Paying users in a native token to use your product isn’t entirely new either—FCoin failed spectacularly at this.

It’s the combination of these two things that have driven the current mania in DeFi.

The theoretical improvement that yield farming brings is a broader distribution where the people who actually use the protocol get to be involved in the decision-making process and capture some of the financial upsides. The example thrown around a lot in 2017 was, “imagine if Facebook’s earliest users got to capture some of the value they created.”

It’s hard to disagree that this is a better state of affairs than a few VCs and accredited investors reaping all the rewards of something they may never use. However, as it currently stands, yield farming is ripe with perverse incentives, lofty valuations, big promises, and multiple layers of risk.

One well-documented set of gameable incentives comes from some of the early activity on Compound following the release of $COMP.

Big Players, mainly this person and this one, exploited the BAT and ZRX markets to farm large amounts of COMP. BAT and ZRX had very steep interest rate curves, meaning they generally have a higher interest rate than other markets at the same utilization ratio (borrows/supply).

Since COMP rewards paid out according to dollars paid in interest, those two accounts supplied large amounts of BAT and ZRX on Compound, then borrowed BAT and ZRX as much as possible to drive the interest rate up.

After they did this, they could supply their borrowed BAT and ZRX back into Compound, and repeat the process — this is called recursive lending. This process doesn’t provide much good for the Compound protocol either. The liquidity they’ve put into Compound isn’t accessible by other users, since they borrow back most of the liquidity they’ve supplied.

Compound fixed this perverse incentive by changing the reward calculation, but this is an excellent example of rewards exploitation with no benefit to the platform.

Another set of incentives and promises comes from a trading opportunity that Alameda Research took advantage of with the Balancer Protocol. As Sam Bankman-Fried documented on Twitter, Alameda was able to game the Balancer Protocol and should have received a ton of $BAL as a result. However, by decree of Discord chats, Balancer decided to enact a whitelist, meaning Alameda would not receive the rewards.

What Alameda showed here was that it would be possible to provide two assets that no one would particularly want to trade between (i.e., they could provide relatively little value to the protocol) while still reaping the bulk of the protocol rewards.

Ideally, the whitelisting decision would have happened via some sort of governance mechanism, but since at the time, BAL was only a vanilla ERC-20 token, the decision had to happen in Discord.

As we covered in a prior post for Deribit Insights, the growing complexity of yield farming incentives and DeFi’s “money legos” leaves users more vulnerable to hacks.

The more layers away the user is from their own money, the more likely it is for a security flaw to exist. Additionally, it becomes more and more difficult for aggregators to audit the entire ecosystem when things become more and more intertwined. The BZX hack was a great example of what happens when multiple pieces of DeFi get mixed together.

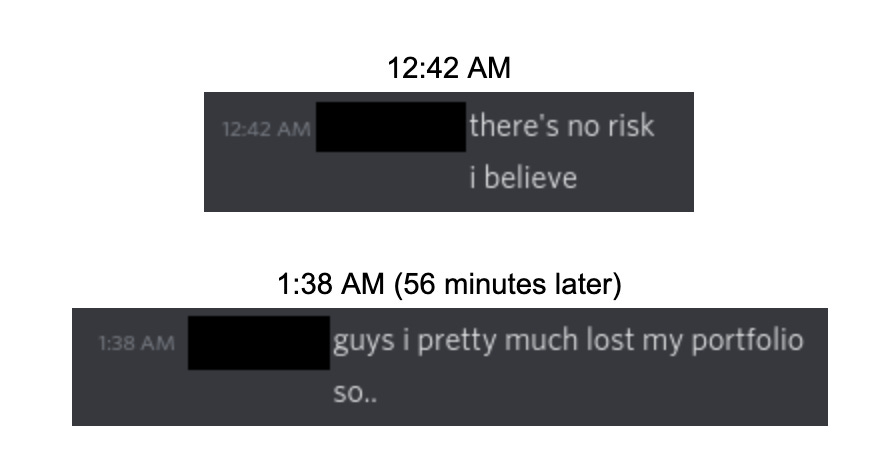

Sadly, users do NOT look at risk enough. It’s easy to get caught up in a frenzy when you’re reading Tweets about 1,000% returns, but then you wind up further down the risk spectrum, until:

All that said, we remain excited about everything happening in DeFi and realize that right now we are probably in the “as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance” phase of yield farming.

There is certainly money to be made in the short to medium term.

The Silicon Valley startup accelerator Y Combinator goes by the simple motto “Make something people want.” The same applies to companies in DeFi. Compensating users with a token whose value only goes up, is an easy way to gain more users and AUM.

But, when the music stops, is the product still something that people want?

First published on August 27, 2020