This post originally appeared on Substack as a part of my newsletter, East Meets West.

Introduction:

If you could only use 1 application on your phone for the next month, which would you choose? iMessage? Amazon? Safari?

WeChat (Wēixìn/微信), developed by the Chinese internet giant, Tencent, is a SuperApp with origins as a messaging app. Today, WeChat contains messaging, social features, payments, travel booking, virtual doctors, and so much more.

WeChat is one of the most used applications in the world. WeChat has more than 1 billion daily active users, putting it into the highest tier of social apps. For a social app, WeChat’s active user count is only surpassed by Facebook.com, WhatsApp, Facebook messenger, and YouTube.

(If you’ve ever opened the WeChat app, you’ve seen this image)

History

*Note… I use Weixin as WeChat throughout this post, but it’s worth noting there is some difference. For example, if you are using WeChat outside of China and don’t have a Chinese bank account, a lot of features are not available to you.

In 1994, WeChat’s eventual creator, Zhāng Xiǎolóng (English name: Allen Zhang), finished his master’s degree in ‘telecommunications engineering’ at Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

By 1997, at 28-years old, Zhang as a lone software engineer created one of China’s earliest internet companies, Foxmail, which became China’s #1 free internet client. It gained about 5 million users which, in 1997, gave it a 33% market share in China.

In 2000, Boda China, an internet services company, acquired Foxmail for ~$1,500,000. Zhang became a Corporate VP at Boda, in charge of technology development.

By 2005, Foxmail has stalled out within Boda with users disappointed at the lack of updates coming from the product. In March 2005, Boda was bought by Tencent or Boda sold Foxmail’s assets to Tencent, details are fuzzy. Either way, Allen Zhang wound up at Tencent.

This was during a period where Tencent was fiercely competing with Microsoft’s MSN and Hotmail to win email in China and the acquisition was seen as a way to strengthen Tencent’s existing QQ Mail offering.

After moving over to Tencent in 2005, Allen was made the head of Tencent’s Guangzhou R&D center and eventually the head of QQ Mail. By 2008, his team had launched a completely revamped version of the QQ Mailbox that supported 2G attachments leading to it gaining in popularity. By March 2008, it was China’s most popular email product.

But by 2010, Allen was beginning to get bored at Tencent.

(Source)

Then, on October 19, 2010, Kik Messenger was released on Android, iPhone, and Blackberry. Within 15 days, the app had been downloaded over 1 million times by users across the world. The value proposition of Kik was pretty simple: free text messaging. It’s hard to remember, but there was a time when you had to pay for text messages. Kik also had features that were very new at the time, including tracking when a message was sent, delivered, read, and when someone was typing, turning texting into real-time conversations.

This period was also the peak era of China copying foreign technology startups and bringing them to China. Within months of Kik’s rise, several Chinese messaging apps were built that copied Kik’s feature set, including apps such as Miliao/Mi Talk by Xiaomi.

Allen was excited by Kik’s fast rise. In October of 2010, Allen sent an email to Pony Ma (Tencent’s Founder and CEO) in the middle of the night expressing his interest in building a similar product,

One night, [Allen] was looking at Kik-like software, [and Allen] came up with an idea: the mobile Internet will have a new IM in the future, and this new IM is likely to pose a great threat to QQ. After thinking about it for an hour or two, he wrote an email to Tencent CEO Ma Huateng Pony, suggesting that Tencent do this. Pony quickly replied to the email expressing his agreement with this suggestion. Allen then suggested to Pony the Guangzhou R & D department to undertake the development of this project. “It’s research-oriented anyway, no one knows what will happen in the future,” Allen recalled. “The starting point of the whole process is an hour or two. Suddenly I took the wrong nerve and wrote this email and it started.”

Pony Ma allegedly responded “马上就做” (Do it now)”

At this point, Tencent already had a massively successful desktop chat app, QQ, the #1 messaging app in China. QQ had a smartphone version, but it was a poor app and not Tencent’s top priority. A lot of the poor development of QQ Mobile was due to internal politics within Tencent. Mobile and desktop QQ were run by different, competing teams.

By November 2010, Allen Zhang had assembled a small team and they had a prototype of WeChat 1.0, which was largely a copy of Kik, with only text message functionality. WeChat launched in January 2011 to little fanfare.

In the background, while Kik was doing great in many parts of the world, it wasn’t gaining much market share in China.

There was a key insight that Kik and WeChat were missing that another startup, Talkbox, would discover. In an interview, Talkbox co-founder, Heatherm Huang tells a story about trying to get his Chinese parents to text with him and realizing that it was difficult for them to type using roman characters.

Many older generations in China, Korea, Japan, and other countries that use a symbol-based writing (你好)system never learned how to type using roman characters. The romanization of Chinese characters, called Pinyin (translating to “Spell Sound”) was only developed in the 1950s and wasn’t adopted as an international standard until the 1980s.

With this insight, Talkbox launched as a walkie-talkie-like application that allowed users to send voice messages between each other. Talkbox was launched a few days before WeChat and exploded in popularity in China.

By April 2011, Talkbox had over 1 million users and was the most popular social app in China and Southeast Asia. According to Talkbox’s co-founder, Pony Ma and Allen Zhang were active users of Talkbox having downloaded the app in its first weeks of launch.

The lackluster response to WeChat 1.0 led Tencent to believe the app would not be a success so they spoke to TalkBox about investment/acquisition. TalkBox turned down the offers.

Before starting TalkBox, Heatherm Huang recalls seeing Pony Ma speak at a conference. Pony Ma shared that even though he had built China’s most successful messaging app (QQ), he was paranoid that his empire could still be destroyed. He hoped that if something was going to kill QQ that it be built by Tencent.

In the summer of 2011, WeChat Version 2.0 launched copying Talkbox’s features to enable voice notes in the chat. With that, WeChat was off to the races.

WeChat 2.1 included the ability for users to connect to their QQ contacts and import them into their WeChat account. Given that QQ was already China’s largest desktop messaging app, this allowed WeChat to port over the strong social grid that Tencent had already built on QQ.

Between the summer and October of 2011, WeChat reached about 30 million users, whereas TalkBox stalled out around 10 million. At this point, Tencent put all their resources behind the WeChat team and began taking resources away from QQ. Heatherm, Talkbox co-founder, shares that during this time, Talkbox made the mistake of trying to fight a war with Tencent and WeChat in China rather than doubling down on their other markets throughout Southeast Asia.

WeChat 2.5 included some social features that helped to grow the app virally, including a “nearby” feature where users could see the avatars, names, and distances of people near to them. WeChat doubled down on these social connectivity features to continue to drive growth.

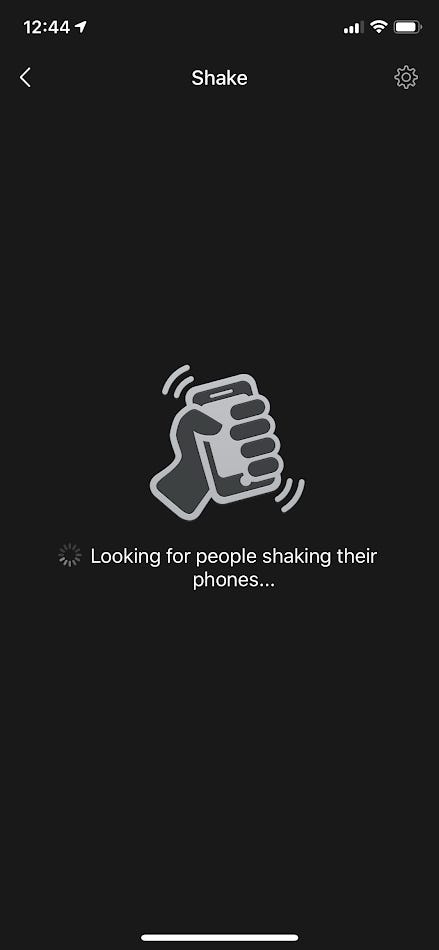

WeChat 3.0 debuted in October of 2011 including “shake” and “drift bottle” features. Shake became a hugely popular feature whereby shaking your phone would match you with another WeChat user who was also shaking their phone at the same time. (This feature still exists. I just tried it out and matched with a woman 383 miles away.)

Per QZ,

“WeChat really became popular because of its ability to connect strangers. In 2011, WeChat rolled out its “shake” feature, which allowed users to shake their phones and connect with other users who were doing the same at that moment. That’s an inspiration from QQ’s “drift bottle,” a hookup feature allowing users to “throw” bottles containing either a text or voice message into a virtual ocean or “pick up” floating ones on QQ’s email service.”

I read an article that described Allen Zhang as a sort of poetically lonely person. In one interview, he spoke lovingly about these features that increased human connection, viewing WeChat as a way to bridge the loneliness that many people felt.

By the end of 2011 and with more than 50,000,000 users, WeChat launched Version 3.5, which included a critical piece of WeChat infrastructure, the QR code (which I learned stands for “Quick Response Code”). In this launch, WeChat gave each account a unique QR code so that if you scan someone’s code, you could easily add them as your friend. Businesses could also register QR codes in which users could scan to view businesses’ catalogs and interact with their businesses in other ways.

Three months later on March 29, 2012, 14 months – or 433 days – after V1.0 launch, WeChat crossed 100,000,000 users. For comparison, of what it took other top social apps to reach 100M users:

WeChat’s next big release, Version 4.0 added “Moments” and birthed its English name “WeChat”. At this point, Weixin (pronounced approximately “way-shin”) had 100 million users, mostly in China, and the company decided that to open up to a more global audience, it needed an English name. Thus, “WeChat” was born.

Some context on Moments: In the background of the development of WeChat, Tencent had been fighting another war against Sina Weibo. Sina Corporation’s Weibo (which means “microblog”) is a Twitter-like product that allows users to post short tweets/microblogs (big oversimplification). By leveraging their QQ social graph, Tencent was able to amass a large user base for its Weibo product which they launched 8 months after Sina’s launch. Ultimately Tencent fell short. In a 2012 earnings report, Tencent said, “As the slow pace of Chinese Weibo user growth, we are seeking an integral point for Tencent Weibo and WeChat, so as to manifest our characteristics”

Thus, I believe Moments was built largely because Tencent failed to create their own killer Weibo app. (This wound up being a great failure)

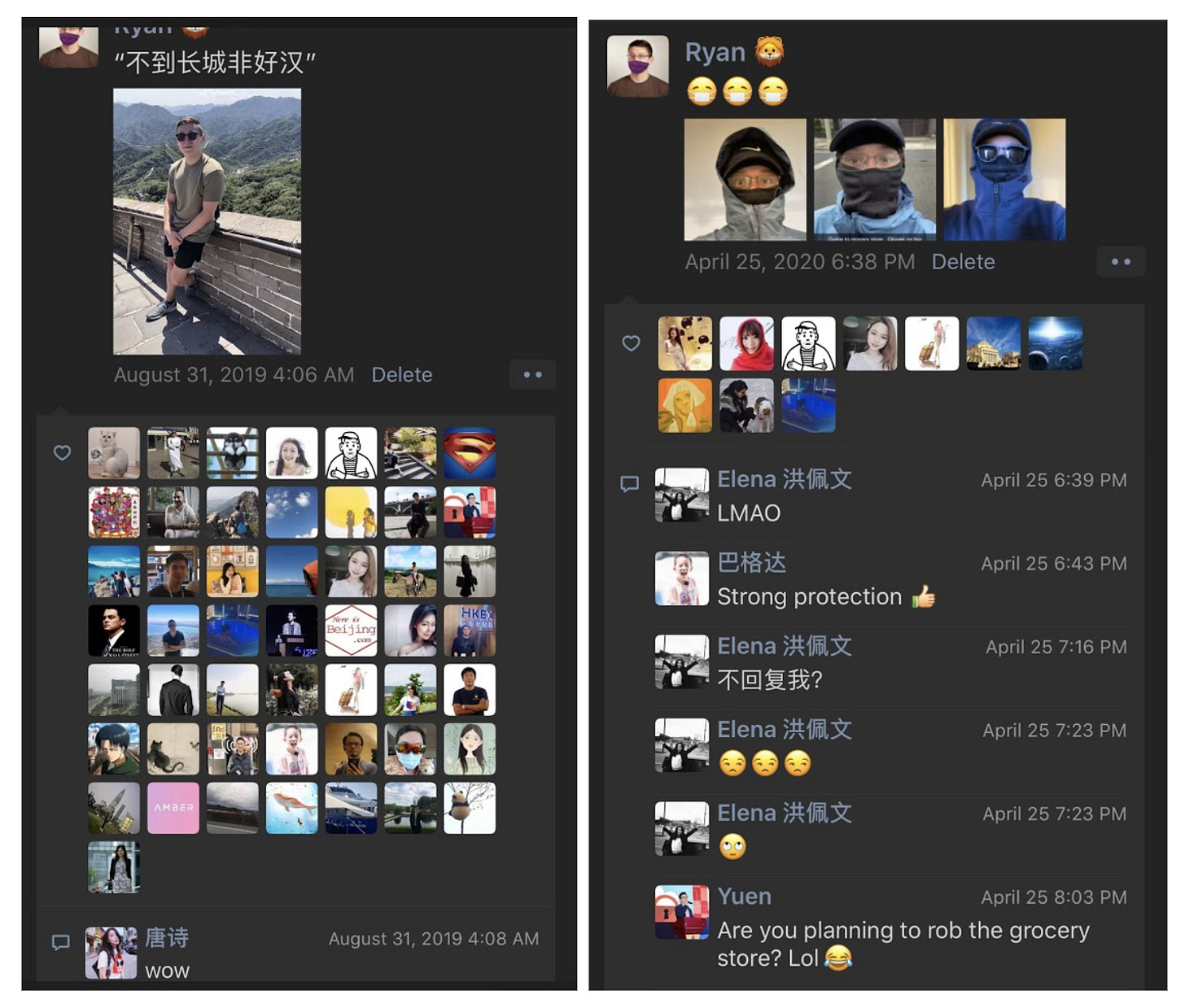

Moments is a social tab within the WeChat app built around the principle that “my friend’s friend is not my friend”. In practice, this means that if I post a photo or status update on my Moment’s feed, only my friends can see, like, and comment on my Moment.

There also isn’t a unique link for Moments (i.e. https://twitter.com/RyanRodenbaugh is my Twitter, but there is no WeChat.com/moments/ryanrodenbaugh).

Here are some of my Moments and what they look like in the latest version of WeChat:

The one on the left shows you what the “likes” look like, whereas the one on the right gives a better look at the comment functionality. In the photo on the right, the person who commented “LMAO” is not friends with any of my other WeChat friends so no one besides me can see her comments or the fact that she liked my photo. In the photo on the left, the woman who commented “wow” shares a bunch of mutual friends with me so all of those mutual friends can see her comment (how nice of her!!).

To make a western comparison, I would describe Moments as a cross between Twitter and Instagram. The scrolling experience on Moments feels like scrolling Instagram where I am only seeing the content of people I follow (i.e., no RTs). Also, the commenting and liking features look more like Instagram. The content on the feed feels more like Twitter though where it is a mix of pure text, articles with commentary, and photos. The one caveat is that, in general, the content I see from my friends on Moments tends to be more personal (photos of them with family, at a dinner, of their cat) than what my friends post on Twitter.

In May of 2013, WeChat introduced Version 5.0, which was focused on B2C offerings and monetization. WeChat debuted official/public accounts, games, an updated QR code, and payments (!!).

With more than 300 million users, WeChat still did not have a firm monetization strategy. Games were their first approach. They added 11 games (games are Tencent’s bread and butter) into the WeChat app. The games allowed for in-app ‘virtual currency’ purchasing.

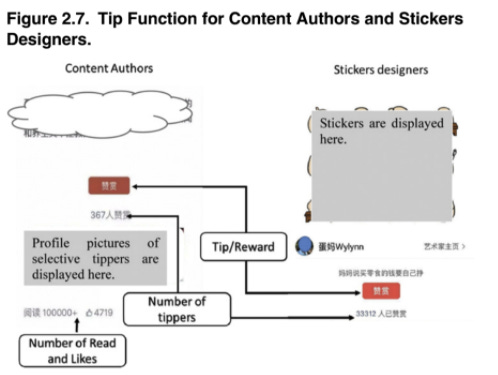

From early on, WeChat was a fan of working with partners and splitting revenue when possible. Two of the eleven games came from developers other than Tencent and had a revenue share agreement included. Around this time, WeChat also added a “sticker shop” where external designers could receive a cut of revenues that came from selling their digital products. Designers’ split ranged from 40-70% of revenues depending on how much was sold.

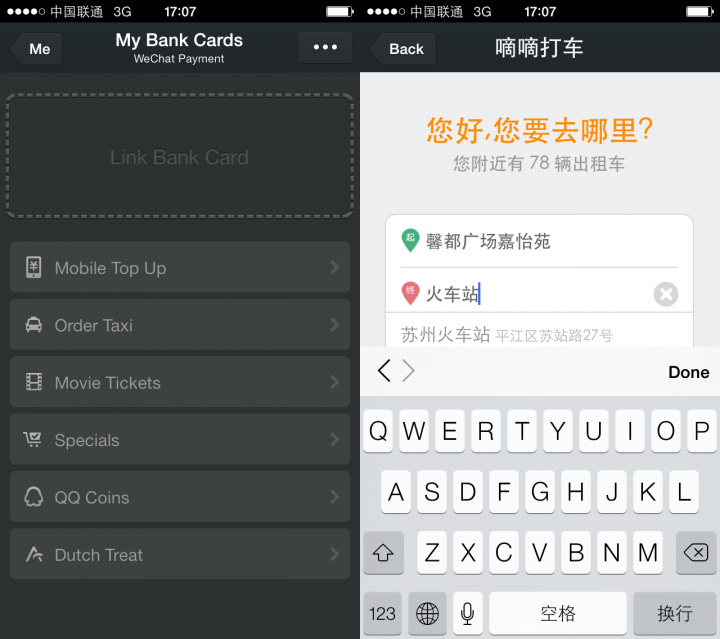

This was the first(?) instance where WeChat where users were able to link their bank account to “WeChat Payments” enabling in-app purchasing for games and digital goods.

Version 5.0 also saw an improved QR code that included “scan to translate”, the ability to scan barcodes and then place online orders for the product, and the ability to scan QR codes to make payments.

The other update in V5.0 was the release of official/public accounts. These were blog-like official accounts for brands and influencers with a lot of functionality for businesses, brands, and influencers to interact with consumers. Some examples that were published at the time included:

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when WeChat became a “Super App”, but this feels like a good point to consider. On my phone right now, I have separate airline apps, package tracking apps, and banking apps. If I was Chinese/living in China, I would not need those. These “official accounts” would evolve into something much bigger, but this is the first point at which brands could build their business (and customer touchpoints) on top of WeChat.

Around this time, WeChat also began partnering with physical businesses to offer online store functionality where in-person businesses could set up a digital storefront and sell goods. Their first pilot was with a Chinese department store. They also tried something with McDonald’s where you could buy a coupon voucher within WeChat and then show the QR code to your McDonalds Cashier to redeem the offer.

By Q3 2013, WeChat had more than 600 million registered accounts with more than 100 million overseas users and 271.9 million monthly active users. For perspective, in February of that same year, they had 300 million registered users.

In WeChat’s December 2013 update, Version 5.1 focused on payments.

In addition to in-app game purchases, users were able to use WeChat pay for phone bills, digital lottery tickets, shopping on Tencent’s online retailer Yixun, purchases at a Ubox vending machine, or Haidilao, the most famous hotpot chain restaurant in China.

WeChat also upgraded the public accounts to have “services accounts”. These were brand focused accounts where brands could message their users directly (think of it as a CRM). Service accounts were limited to only sending one bulk push marketing message per month to reduce users feeling cluttered or spammed. This inclination to limit messages from brands stems from Allen’s deep love of product and his insight that brands spamming users would ruin users’ relationship with the WeChat product.

WeChat saw the importance of payments and employed some good old growth hacking techniques to get more users to connect WeChat to their bank accounts.

In December 2013, WeChat allowed users to make group chats of 100 people but each user could only be the owner of one 100-person group. To promote WeChat Pay adoption, WeChat allowed users to own another two 100-person groups after having signed up for WeChat Pay and an additional fourth group if the user used WeChat Pay. This was notably different than how Tencent’s QQ desktop messenger worked where users would have had to have paid for a premium subscription if they wanted to have large group chats.

WeChat also added the ability for users to have default shipping addresses, making shipments (and the payment process) more seamless.

Back in the Spring of 2013, Tencent made a $15 million-dollar investment in the then-nascent Chinese ride-hailing app, Didi, buying a 20% stake in the company. On January 2, 2014, they invested another $30 million into Didi as a part of a $100 million round (today, Didi is valued at ~$50-60 billion).

A few days after their second investment in Didi in January of 2014, WeChat and Didi announced a partnership where on the WeChat Pay page, you could directly “order a taxi” using Didi’s service. As a promotion, users who paid with WeChat Pay had a 10 Yuan (~$1-2) subsidy applied to their rides. For WeChat, this gave users a great reason to set up their WeChat Pay given that Didi had a ~60% market share in Chinese ride-hailing at the time. For Didi, this gave them more direct access to WeChat’s hundreds of millions of monthly active users. The promotion was a big win, with some large cities like Wuhan (a population of ~11 million) seeing 60% of DiDi users switch over to WeChat Pay.

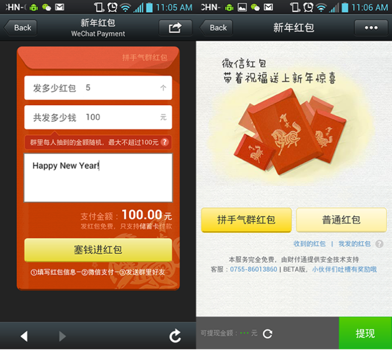

During the Chinese New Year (late January) it is a tradition for family members to give each other 红包 🧧 (Hong Bao, Red Envelopes) with a little bit of money inside.

During the 2014 CNY celebration, WeChat enabled users to send hóngbāo to their WeChat friends. You could (and still can) either send an envelope directly to a friend or to a group of people where they can split up the monies. The best part for WeChat? To send or receive the money, you needed to be signed up with WeChat Pay.

During the 2014 celebration, it led to hundreds of millions of red envelopes being sent and more importantly, brought the number of WeChat Pay users from 30 million to 100 million. Funny enough, WeChat Pay’s main competitor, Alipay (by Alibaba) launched a similar feature two years earlier, but it never took off the way WeChat’s feature did. Alibaba founder Jack Ma called it a “Pearl Harbor moment” for his company.

Red envelopes also had a cultural subtlety that made them very attractive. Chinese people enjoy gaming and gambling. Red Envelopes built both of those aspects into the product. For example, when you send an envelope,

“You can put $5 in a red envelope and [send it to a group chat with 5 people and] set it to disburse equally, so each friend gets $1. Alternatively, you could stipulate that the first two people to tap will get all the money in equal portions—$2.50 each—or that the first two people get a random cut, maybe $1 for one person and $4 for the other. The result is that any time a red envelope appears, people scramble to tap on it as fast as possible”

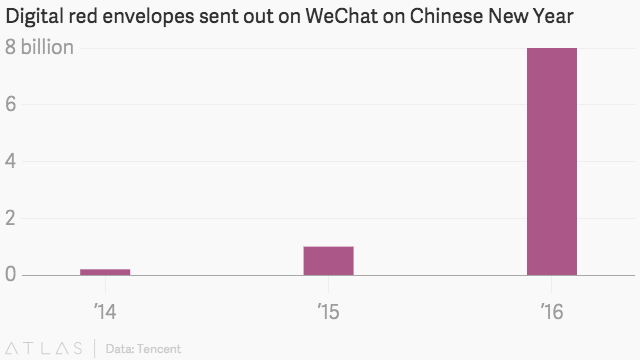

During the 2015 Lunar New Year, ~1 billion red envelopes were sent, and by the 2016 Lunar New Year, WeChat logged ~8 billion Red Envelopes sent.

Source: QZ

Like how Tencent had a popular messaging app (QQ) before WeChat, they also had a payments app (“TenPay”) before WeChat Pay. TenPay was always smaller than Alipay, but with the penetration of WeChat’s users and promotions via WeChat Pay, WeChat Pay was able to compete against Alipay in a way that “TenPay” was not. (FWIW, TenPay still exists and sometimes analysts will use TenPay interchangeably with “WeChat Pay” since I think it is technically the same infrastructure/digital banking license)

In 2014, WeChat upgraded their services pages to allow brands to set up stores within the WeChat app (originally called “WeChat Little Store”). Consider these like mini-Shopify-Esque pages within the WeChat app. Stores could upload and manage items, show inventory, receive payment (via WeChat Pay), and ship products to users. This was around the same time that Tencent gave up on some of their e-commerce ambitions and secede to JD.com, taking a large ownership stake in JD in the process.

Commerce is uniquely smooth within WeChat because payments are so deeply integrated into the app. These “WeChat Little Stores” did a lot to turn WeChat into a commerce search engine. Rather than e.g., going to Baidu and searching “Nike” and then going to their site, putting in payment info, shipping info, and making a purchase, you can just search Nike store on WeChat and payments and shipping info are also integrated. It’s a storefront built on top of a payments app, rather than a payment experience build into a website.

By June 2014, SMS texting was basically declared DEAD in China. It was reported at the time that the average Chinese person sent about 1 text/day in a period when China added 27 million new phone subscribers.

In July 2014, Tech in Asia published an article foreshadowing the growing trend in China of entrepreneurs choosing to build their apps solely on WeChat and not bothering with iOS and Android applications. Though there are tradeoffs to not having your own app, one founder said, “With 400 million active WeChat users, getting access to them outweighs any cons.”

One year after adding payments, WeChat was already persuading founders to build their applications solely on their platform.

Very similar to Shopify “arming the rebels”, WeChat saw that it was expensive for retailers to get noticed on big e-commerce platforms in China like JD, Taobao, etc. WeChat gave merchants a direct way to sell to their consumers.

In September 2014, WeChat Pay added the massive feature of allowing users to pay for in-store purchases with QR codes. Initially, this feature was only supported by large merchants (e.g., Dairy Queen), but in 2020, virtually every single vendor in China from taxis to street vendors to Gucci stores support QR payments via WeChat Pay (and AliPay, which came to market with this QR code feature a few years before WeChat Pay).

By Q4 of 2014, WeChat crossed 500 million global monthly active users, up from 355 million in Q4’13.

WeChat also continued to push their monetization by allowing ads to show in the “Moments” feed. Anecdotally, as an active scroller of “Moments,” the ads have never once felt intrusive or annoying.

Around 2015, WeChat implemented what I found to be one of their coolest features and it is a testament to what you can do when you have deeply integrated payments. Public accounts were able to add a “tipping” feature or put a paywall in front of their content. Online tipping is a huge industry in China with lots of streamers and content creators monetizing their content this way. With two clicks, you can tip content creators on WeChat. Easy as that. By 2017, about 11% of WeChat users (that’s a lot of people!) had used the function. Tencent would eventually run into problems with Apple’s transaction policies for iOS users, but more on this later.

In April of 2016, at a time when Slack was valued at about $3.6 billion, WeChat launched WeChat Enterprise (later renamed WeChat Work). At first, the offering included all of WeChat’s core features (chat, voice messaging, send location, etc.) with the addition of work-related features such as requesting time off.

I believe one of the reasons they did this was that many people were already using WeChat for work, but because they now had so many work-related chats and contacts, people might have started feeling hesitant posting to Moments. A personal anecdote to support this… I made a WeChat account because I was doing a lot of business with people in China. For me, WeChat was first a business app, but over time as I made more and more Chinese friends, I also had a lot of personal relations on the app. I’ve always posted personal and funny things on my Moments (as you saw above), but I had a lot of friends who said that because they had so many work friends on their personal account, they posted less on their Moments. On that note, it’s also not uncommon for people to have multiple WeChat accounts (one for family and close friends and one for work-related contacts)

As of February 2020, 60 million users across 2.5 million organizations were using WeChat Work (all in China, btw). It was reported that 80% of China’s Fortune 500 and 81% of the top retail organizations in China used WeChat Work (wow!). They’ve also added all the other features you’d come to expect from an offering of this kind (file sharing, expense account management, etc.)

For comparison, Microsoft Teams had 75 million daily active users (32 million pre-COVID) and Slack’s last public number in October 2019 was 12 million DAU.

Throughout the 6.0 Version upgrades of the WeChat core app, the updates were largely nice to have features e.g., group video calls, WeRun (a Strava-like product), etc.

One of WeChat’s biggest product additions came in early 2017 with the formal introduction of “mini-programs”. By this time WeChat had 846 million monthly active users and 768 million daily active users.

Mini-programs are “light apps” (though Apple wouldn’t let WeChat call them “apps”) that lived inside of the WeChat application. While some of the apps are from independent companies (e.g., a startup that makes a camera filter app), many of them are created by brands who want more ways to interact with customers. For example, Nike has a mini-program that looks like a full-fledged store, McDonald’s has one for coupons, movie theaters have mini-programs to buy tickets, and Didi has one to get a ride.

One year after launch in January 2018, there were 580,000 mini-programs on WeChat with 170 million daily active users. By the end of 2018, mini-programs had 600 million monthly active users and it seems about 200 million were daily active users.

In 2019, mini-programs weren’t just appealing to big brands like Nike, but also to the long tail of stores, “Niche apps within WeChat, such as those used by a parent-teacher group or neighborhood grocery store, accounted more than half of total Mini Programs traffic.”

You could think of it like, in the US, we have Slice so that pizza store owners can have a digital presence with delivery and Joe.Coffee for coffee shop owners to offer a mobile experience… but in China, every single physical store can have a digital presence through a Mini-Program. That analogy isn’t perfect, but it approximately frames the situation.

Something that sets WeChat mini-programs apart from regular apps or foreign equivalents is that by default, it is integrated with all other parts of the WeChat ecosystem: payments, live streaming/video, ability to interact with offline QR codes, geo-location, social connections, notifications, and all the other WeChat features. As a Tencent executive said at a conference, “Just build a good Mini Program, and we’ll do the rest.”

Tencent shared in its 2019 annual report that the number of daily transactions within mini-programs doubled YoY and that the total 2019 transaction volume exceeded RMB 800 billion ($112 billion).

Most WeChat programs fall into three overarching buckets, games, e-commerce, and lifestyle (which admittedly is a catch-all for everything from ride-hailing to cleaning services). Some examples of the diversity of WeChat programs are:

One of the reasons Baidu (“Google of China”) has dreaded WeChat and mini-programs so much is that mini-programs have strong SEO, leading a lot of Chinese people to start their searches in mini-programs. For example, if you wanted to buy new running shoes, you might start that search in WeChat mini-programs rather than Baidu. This is a partial explanation for why Baidu stock is down 50% from its all-time high.

WeChat Launched 6.0 in late 2014 and then took about 4 years before launching 7.0 in January of 2019. In that intervening period, WeChat continued to grow at an incredible rate across it’s messaging features, payment features, mini-programs, etc. but they did not add many new features during that time. There were few updates to Version 7.0, which speaks to more of Allen’s product principles of keeping things simple and not changing too fast on users.

I remember reading the book “House of Lies” about management consulting where a non-McKinsey consultant is feeling envious of McKinsey and is trying to get McKinsey out of his mind. As he goes through his day, he realizes everything he interacts with has some connection to McKinsey. He goes to brush his teeth, but the Colgate CEO is ex-McKinsey, he puts on his shoes and the shoemaker CEO is ex-McKinsey, and so on.

In China, you can have a similar kind of day all where all your interactions touch the WeChat app.

You get the point.

The evolution of WeChat can be seen as “Social App” —> Platform —> Operating system

Though WeChat did not invent the idea of a ‘Super App’ (more on that in a later post), they are the first incarnation of the concept. My prior two posts on Gojek and Grab are examples of companies who are trying to brand themselves as and become full-blown Super Apps, inspired by what WeChat has done.

That said, there are a lot of subtleties to WeChat that made it especially poised to be the world’s first and biggest Super App. More on that in the next post 😉

(If you got this far, thank you so much for reading ❤️)

This post was getting very long, so I broke it into two parts. This post (part one) covers the history of WeChat, chronologically going through its founding story and product evolution. Part two will cover some of the themes of WeChat.

First published on July 19, 2020