This post originally appeared on Substack as a part of my newsletter, East Meets West

Follow me on Twitter: @ryanrodenbaugh

I’ve learned many things while writing East Meets West. One of the top learning is that Tencent is one of the world’s best technology investors. A few weeks back I started putting together a sheet to map Tencent’s ownership stakes in other companies. I was quickly overwhelmed.

From a 5% stake in Tesla to a 40% share of Epic Games, Tencent knows how to invest, leverage its distribution, and make connections in China to help companies enter and win in 中国 (the middle kingdom).

As Niko Partners points out in a report, in just gaming, Tencent has 30+ investments in basically all the major game developers.

Today we’re talking about Tencent Music Entertainment Group, its relation to Spotify, and what the future of Spotify might look like.

Throughout the article, I refer to Tencent Music Entertainment Group as “Tencent Music”, “$TME”, “TMEG”, and “QQ Music”.

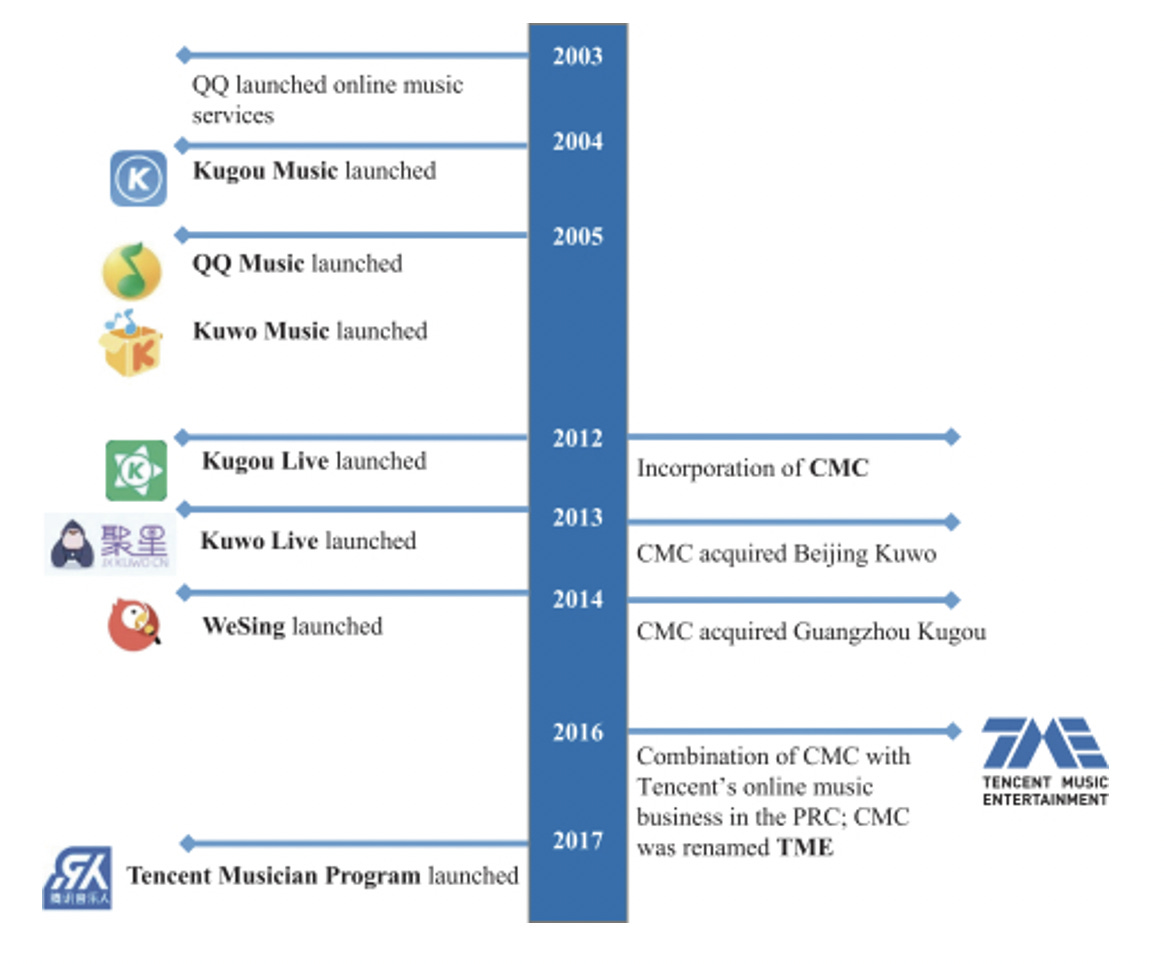

Around the launch of the iTunes Music Store in 2003, Tencent’s QQ messenger (somewhat of a precursor to WeChat, covered briefly in an earlier issue) launched music services.

In 2005 music services were spun out into a standalone product, “QQ Music”.

Between 2003 – 2006, several other music/MP3 services launched in China, including, Kugou, Kuwo, Xiami Music, and Baidu’s MP3 service.

In the decade between 2003 and 2013, China’s music industry was characterized by rampant piracy. By 2013, even though China had more smartphone users than any other country, the country contributed almost no revenue to the music industry.

In 2014 Tencent began inking partnerships with record labels, specifically Warner Music and Sony, earning the right to manage the online distribution of music in China for two of the world’s largest music companies. However, after a decade of Chinese music lovers becoming accustomed to free music, it was tough to get them to pay. In 2014, QQ Music only had 2.8M subscribers paying RMB 10 ($1.60) per month for ad-free streaming.

From the perspective of the entertainment companies, this was still a great first step at opening up content monetization in China. One of the unique things about the deals with Tencent is that while it gave Tencent exclusive distribution rights, Tencent also agreed to sublicense the rights to other streaming companies, often at a hefty markup.

Regardless of the sub-licensing agreements, it is clear why Tencent would be the ideal partner for a content company. Tencent could offer foreign companies more distribution and monetization options than any other company in China.

For example, with Warner:

“While QQ Music can feature Warner’s artists more prominently, Tencent’s concert-ticketing service can also launch promotions when Warner artists tour in China.

JD.com Inc.—China’s second-largest online shopping company, in which Tencent has a 15% stake—could sell digital music, T-shirts and other items from Warner musicians, the people said.”

Tencent offers foreign partners the ability to plug into the Chinese market via its many distribution (and monetization) channels. In some cases, they can even help you build a factory (especially when 90% of the challenge is political).

One year after the agreements with the record labels, in the summer of 2015, the Chinese government’s copyright agency announced stricter rules on music streaming, giving platforms <30 days to remove unlicensed music. “The administration added that the move was in line with China’s copyright law and regulations. Those who do not follow the order will be seriously punished, it said.” One has to wonder if Tencent was tipped off about this regulation or did some lobbying for its creation.

This was the point at which the music industry in China flipped in Tencent’s favor. Tencent had spent the past year signing exclusive distribution partnerships with two of the world’s big 3 record labels and had a catalog that the rest of the streaming companies in China would struggle to compete with without a full-on bidding war.

But one other company took a similar strategy…

In the background of all of Tencent’s activities, another company, “China Music Corporation” (aka “Ocean Music”) founded by former music industry lawyer, Xie Guomin, was also snapping up music copyright agreements and had an almost equal amount of song rights as Tencent did by 2015. While Tencent signed a few licensing deals with the largest record labels, China Music Corporation (“CMC”) was signing hundreds of agreements with much smaller record labels.

The history of China Music Corporation is a bit murky, but it appears China Music Corporation (“CMC”) had no operations of its own in its early years and was strictly a copyright hoarder of music rights.

In 2013, China Music Corporation, with the support of a private equity investor purchased Kuwo, which at the time was the third-largest streaming service in China.

In 2014, China Music Corporation then also purchased Kugou, the #1 streaming service in China.

(For more on the history of CMC, there is an insane write up from the South District of NY as a result of a lawsuit from China Music Corp’s first investor who was defrauded of his shares and threatened by fake Chinese government agents😲).

Following these two acquisitions, in the summer of 2016, as CMC – now the owner of 2 of the 3 of China’s largest music streaming services – was rumored to be prepping for an IPO in the U.S., Tencent purchased a majority (~60%) stake of CMC. Tencent spun off its QQ Music (along with another property, WeSing) into the new majority-owned entity and renamed CMC as “Tencent Music Entertainment Group”.

The Financial Times revealed that this Tencent / CMC courtship had been going on for about one year prior.

At the time of the merger, this struck observers as odd since CMC was doing about 2x the revenue of Tencent Music. China Music Corporation’s CEO, Xie Guomin, was prescient in describing the merger decision, and given that he previously worked at Sina (a Tencent competitor) he knew how Tencent liked to fight.

Mr. Xie was quoted,

“We have more users today than Tencent, but if they chose to fight, and if they don’t care about the money, they can change their market share very quickly. They can pay ten times more than we can for content.”

At the time of the acquisition

The newly merged entity, valued at about $6 billion, held nearly 60% market share of China’s music streaming industry and crucially represented 60%+ of all available music rights in China.

To this day, Tencent Music continues to operate each of these applications separately. So while QQ Music, Kugou, and Kuwo all offer the same content library, their differences are highlighted in the types of music listened to and the demographics of users on each platform.

But even with record labels striking deals with companies like Tencent and the Chinese government’s 2015 ruling against piracy, there was still limited willingness by consumers to pay for music services.

I believe this opposition to paying for music in China is what ultimately leads Tencent to figure out other paths for monetizing music.

To recap, a brief history of Tencent Music between 2003 and 2017:

In September of 2017, it was reported that Tencent tried to buy Spotify to fuel its international expansion outside of China. This did not happen.

But a few months later, Spotify and Tencent Music Group agreed to swap equity with each other.

“Tencent Music Entertainment Group and Spotify will exchange minority stakes for cash. Parent company Tencent will also buy an additional stake in Spotify through existing shares on the secondary market”

Spotify received a 9% share of Tencent Music Entertainment Group. Tencent (parent company) received a 7.5% stake in Spotify, though, between Tencent and Tencent Music, the two affiliated companies would eventually own about 9% of Spotify, which currently makes them Spotify’s third-largest shareholder.

Spotify CEO, Daniel Ek said,

“This transaction will allow both companies to benefit from the global growth of music streaming,”

As far as I am aware, equity swaps like this are not common (??). This swap made sense in my view because:

“Foreign investors are prohibited from investing in companies engaged in certain online and culture related businesses, internet audio- visual programs businesses, internet culture businesses and radio and television program production businesses.”

This is a genuinely interesting regulation in itself and it points out that it is illegal in China for a company engaged in defining culture to have foreign ownership, as Spotify certainly does.

Now you might say, well isn’t Tencent Music owned by both Spotify (10%) and other foreign investors via its Nasdaq IPO? That’s a topic for potentially a whole other issue, but if you’re interested in the controversial “Variable Interest Entity Structure” (“VIE”), you can take a tangent here.

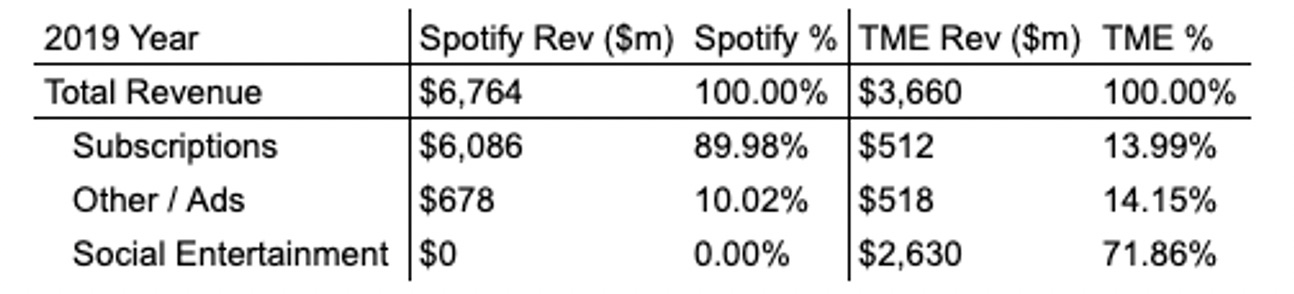

Before diving into this issue, I did not expect Spotify and Tencent Music to be much different. I expected Tencent Music to just be “the Spotify of China”. As I alluded to earlier, while they may look like similar companies, their revenues tell a different story.

Tencent Music borrows more characteristics from its parent company, Tencent than from Spotify. TMEG revenue streams resemble a social, user-generated content company, more than a music streaming app.

Spotify’s business is pretty straightforward, listen for free with advertisement interruptions and other limitations or pay $9.99/month for ad-free listening.

As shown briefly below, for 2019, Spotify made $6.7bn in revenue, of which 90% came from subscriptions and 10% from advertisements. As of December 31, 2019, Spotify had 271M monthly active users, of which 124 million were premium subscribers.

Tencent Music, on the other hand, looks much different. As of 2018, their premium music subscription ranged from only RMB 8-15 ($1.20-$2.25) per month. As a result, Tencent Music has about 1/12th as much subscription revenue as Spotify, even though TME has nearly 3.5x as many monthly active users as Spotify.

While Tencent Music is generating only about $500m/year on subscriptions and $500M/year on ads, it is generating $2.6bn (72% of total revenue) from music-centric social entertainment services

In terms of average revenue per user (ARPU), Spotify’s 2019 Premium ARPU was €4.72 ($5.58) per month. This decreased from the previous year because of the growth in popularity of the Family Plan and an increase in the number of subscribers on free trials.

Tencent Music’s calculates ARPPU (per paying user) rather than ARPU so the number will be slightly higher, but regardless, their premium subscriber average revenue per paying user is still only RMB 9.3 ($1.39) per month. However, Tencent Music’s social entertainment ARPPU is MUCH higher at RMB 138.5 ($20.74)!! And that’s up 10% from the prior year.

So, what exactly are music-centric social entertainment services?

In their IPO docs, Tencent Music describes the “music-centric social entertainment services” category as:

“Primarily include virtual gift sales and premium memberships, both of which are seamlessly integrated into the comprehensive user experience offered by our social entertainment services.

For example, users can send virtual gifts to show appreciation to those who share their karaoke or live performances, providing performers with an effective channel to interact with their fans and an attractive way to monetize their performance.”

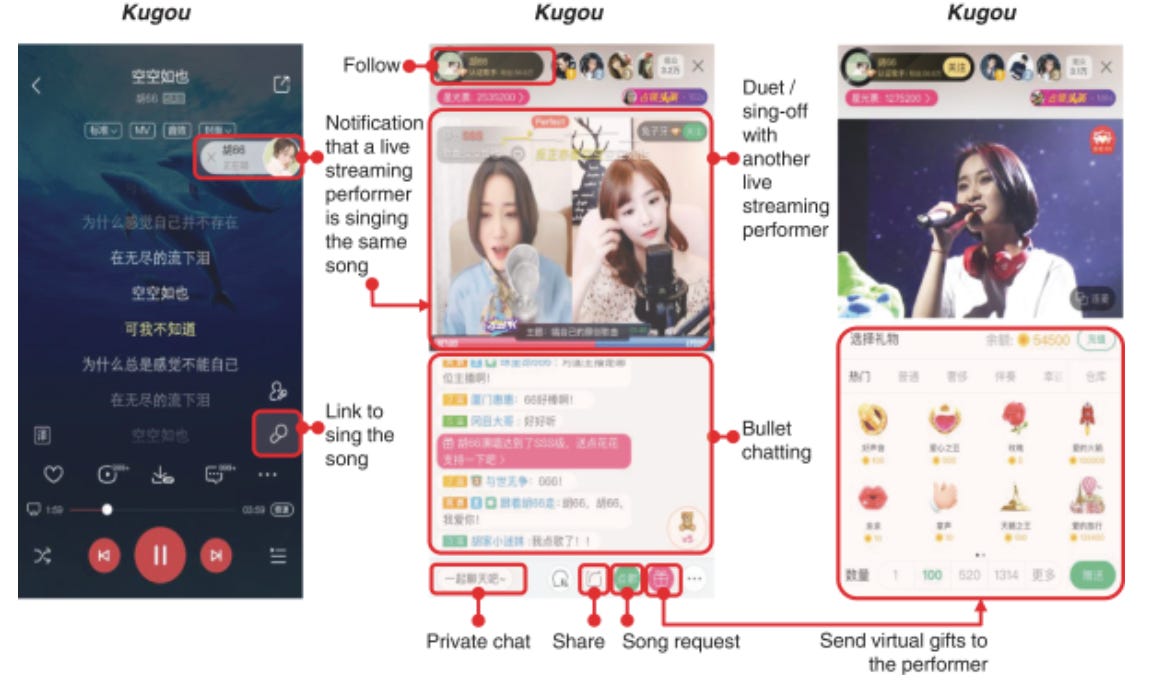

Revenues in these “social entertainment services” are predominately driven from online karaoke and live streaming services where users buy virtual gifts for performers and entertainers along with premium memberships for karaoke and social experiences.

While both Kugou and Kuwo operate services called “Kugou Live” (launched December 2016) and “Kuwo Live” (launched March 2013), the majority of this revenue is driven through WeSing.

Tencent provides WeSing with user traffic and access to the WeChat social graph to turn WeSing into a highly social experience

“We currently require users to register with and access services and functions on WeSing using their Weixin/WeChat or QQ accounts, as WeSing is primarily used by users to socialize with their friends on Weixin/Wechat or QQ through music.

Such linkage between WeSing and Weixin/WeChat or QQ has in turn also enriched Tencent’s content ecosystem by providing Weixin/WeChat or QQ users with convenient access to our content.”

WeSing has a number of functions all built around, well… singing.

On WeSing users can sing duets with pre-recordings of celebrities or other users, have karaoke parties in virtual song rooms, challenge other users in online sing-offs, and request songs for artists or other users to sing live.

WeSing monetizes these functions through the sale of virtual gifts to reward good performances along with premium memberships that come with “value-added functions, such as higher soundtrack resolution, additional app themes, and access to vocal singing tutorial programs”.

Music streaming and live streaming feed very naturally off of each other. As an example, “when a live streaming performer on Kugou Live performs a song, a message bubble pops up instantaneously on Kugou Music notifying users listing to the same song”.

If you were watching a stream of your favorite musician, you’d be able to make a song request by sending them a virtual gift (that you paid for). Similarly, users are able to chat beneath a live stream and receive message priority based on how much they tip via virtual gifts (similar concept to Twitch Bits).

This relatively easy way to engage with and monetize fans seems it would be especially useful for up and coming artists that have smaller, but loyal fanbases.

In some sense, the success of these ‘social entertainment’ revenue streams for Tencent Music highlights a cultural difference between the East and West in terms of content and creator business models (not to mention a difference in their love of Karaoke). Content creators and publications in the West tend to monetize through either subscription or advertising. In China, there is much more of a tipping culture for creators that fit wells with the content produced via Karaoke and live streaming.

I wrote briefly about tipping within China in WeChat Part 2 and the kerfuffle it caused between Apple and Tencent.

“Flashback to 2017 when tipping [for content] was taking off within WeChat. Tencent was not taking any service fees on tips and Apple made them disable their tipping function because Apple considered the tips to be in-app purchases”

It’s actually unclear to me how Apple handles tipping and gifts within Tencent Music apps, but presumably, there is some kind of special agreement there, as well.

P.S., For more info around live streaming and the tipping dynamic in China, check out the documentary, People’s Republic of Desire. It’s free on Amazon Prime Video. This documentary is a much darker view of the dynamic than I outlined above.

In the West, there is a generally under-tapped market by musicians and podcasters (broadly, “creators”) to monetize their audiences.

While platforms like Patreon provide one route for creators to offer exclusive content to their users, it seems this premium content would be better suited natively to a platform like Spotify.

Since Spotify is making a big push on podcasting, I’ll focus a bit more on that type of audio content (rather than music).

For podcasts, popular monetization paths are:

(Similar for music, but swap advertising/subscriptions for licensing/record sales)

The Chinese behavior of ‘tipping’ your favorite creators could be a difficult behavioral change for the average western consumer (though not impossible, given the success of Twitch).

Within podcasting, it seems like the better V1 opportunity is less immediately social than TME, but still trending in that direction.

Spotify could offer the ability to subscribe to your favorite podcasters’ premium feed in-app. This would decrease the activation energy required for a user to start paying for a creator’s content directly. This also begins to open up the door to more social experiences, such as ‘fan clubs’ for creators.

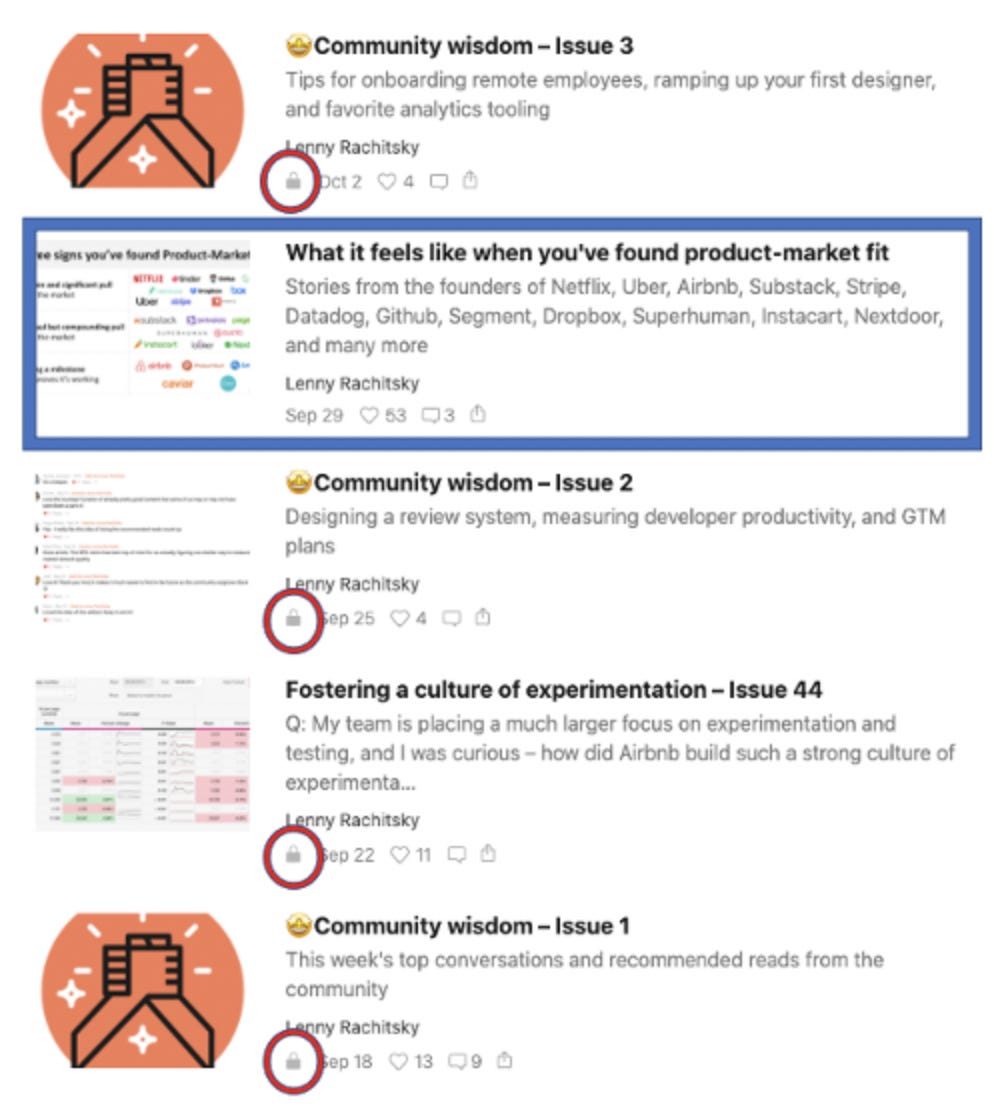

I imagine the experience would be comparable to Substack. Below is a screenshot for a popular paid Substack.

As a non-paying subscriber, I can see that between September 18 and October 2, five issues were published, though 4 of them are locked behind a paywall, whereas 1 is free.

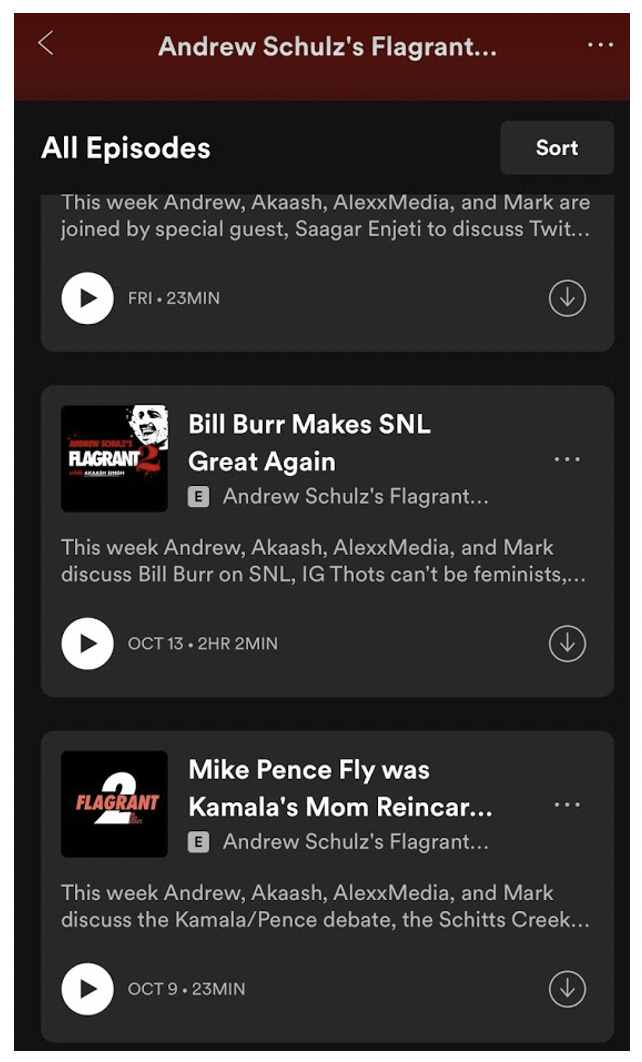

One content creator success story I’ve enjoyed watching during COVID has been the comedian, Andrew Schulz. He’s been doing standup for years, co-hosts a few podcasts, and has a YouTube channel. He’s had a Patreon account since September 2018 and during COVID, his Patreon became the #3 highest-earning, making over $1mm/year.

Below is a screenshot from Andrew Schulz’s podcast feed on Spotify. He offers free content on Spotify and paywalled content on Patreon at the moment.

In a future where Spotify begins offering a paid feed natively, anyone would be able to see that paywalled content exists (like in the Substack example), but not be able to listen without a subscription (perhaps only a 10-minute preview).

People who want to listen will be given the option to subscribe to Andrew Schulz directly (on top of their Spotify premium membership) with a 10-30% cut of that revenue going to Spotify.

Closer to the tipping model, Spotify could also play around with the idea of letting users purchase premium content on an episode-by-episode basis.

Let’s say Andrew Schulz charges $5/month for his premium content and puts out 4 premium episodes/month (so $1.25 per episode). Spotify could offer Andrew Schulz subscribers to listen to individual paywalled episodes for $3/episode. This would give people a cheap way to sample a creator’s premium offerings.

The most notable hurdle here is Apple’s fee on in-app payments, potentially making this less lucrative for Spotify.

Given that Spotify also seems to be making a push for more video content (see: May 2020 beta testing and video being a part of the Joe Rogan deal), this seems like it would be a path for creators to offer either exclusive live streams to paying fans or exclusive video as a part of a bundle of offerings. This would be similar to the ‘fan clubs’ offered within Tencent Music.

I believe COVID + improvements in live streaming (Zoom, etc.) has increased people’s willingness to pay for live digital events.

For example, again in the comedy podcaster realm (which seems to be very innovative), ‘Your Mom’s House’ (a podcast by a comedian husband and wife) has been hosting live video events that cost $10/person. They also built a site (http://ymhvirtual.com/) where upcoming and past event links live. Doing some napkin math, it seems like the average YouTube video for their flagship podcast gets about 500,000 views so if even 1% of that converts to a $10 live stream, that’s $50,000. That number is likely much higher as the 500,000 views undersell their whole reach since it’s not inclusive of people who listen to only the podcast and don’t watch the video.

I believe similar dynamics could exist for musicians. There is added complexity for musicians because of the complex agreements they have with record labels, but let’s assume Kanye West fixes all that, and let’s keep things simple for argument’s sake (and since I’m not a music/legal expert).

Take a look at BTS (the Korean boyband and one of the most popular music groups on the planet). Through the app WEVERSE (a Korean app for hosting content and artist-to-fan comms), BTS hosts its “BTS Army Fanclub” where for between $22-$150 annually you can receive perks such as:

Now I’ll be honest, this does not sound like a great deal. It mostly sounds like you’re paying for the opportunity to buy more stuff.

However, you can envision a better version of this where you can pay $60/year for a ‘fan club’ subscription to your favorite artists that includes e.g., a limited print poster or t-shirt, a few live streams per year, quarterly AMAs with your favorite musician where you (as a subscriber) can pre-submit questions, early access to concert tickets, etc. And this whole, highly social experience would live within the Spotify platform.

On top of $10/month for your regular Spotify premium membership, fans would be another $5+/month for additional content from their favorite artists.

One example from Tencent Music,

“In March, Ms. Ye went to a members-only concert in Shenzhen where TFBoys sang in front of thousands of screaming fans. “I pay because I want to support TFBoys. If there’s anything I can do for them, I will,” she said, waving a banner with the band members’ names.”

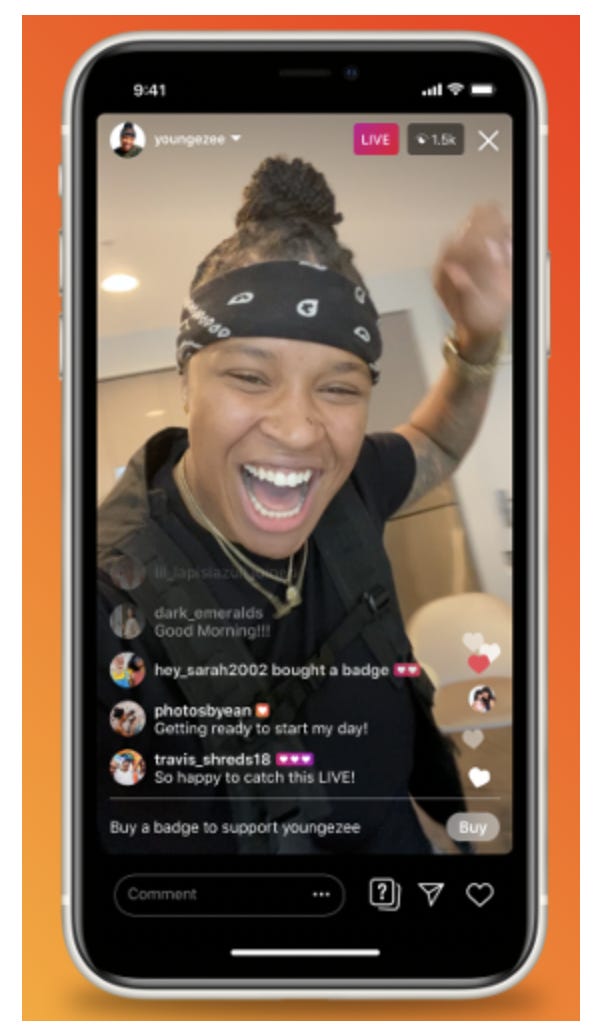

As I was writing this post, Instagram shared that it would begin helping its content creators monetize in new and social ways. Some Instagram live streams will be able to introduce “Badges” that fans can buy to show their loyalty and support. Per TechCrunch:

“Instagram users will see three options to purchase a badge during live videos: badges that cost $0.99, $1.99, or $4.99.

On Instagram Live, badges will not only call attention to the fans’ comments, they also unlock special features, Instagram says. This includes a placement on a creator’s list of badge holders and access to a special heart badge.

The badges and list make it easier for creators to quickly see which fans are supporting their efforts, and give them a shout-out, if desired.”

(Photo: From TechCrunch)

This is another path Spotify could consider, where music and e.g., ‘karaoke’ influencers could leverage Spotify’s music distribution rights to make a brand for themselves on the Spotify platform. This, however, feels like much more of a stretch as this turns Spotify into more of a user-generated content app.

Even though podcasts are mostly user-generated (i.e., not produced by big studios), there is still a barrier to entry in podcasting that is higher than TikTok (which Karaoke videos are more akin to).

Ultimately, there is a wide gap between where Spotify and Tencent Music each currently sit. Spotify does not need to jump all the way across that spectrum but can begin making progress to becoming more social.

As told by their revenues, Spotify is a subscription music service and Tencent Music is a user-generated-content (UGC) company focused on Karaoke and live-streaming with music subscriptions as an ancillary source of revenue. Trying to transform Spotify into a more UGC-driven company would be a step too far, but leveraging their existing partnerships and relationships with creators, they could build new social channels around those individuals and give them new ways to interact with and monetize their fans.

Spotify seems to be taking some steps in this direction, but not with the experiences actually living on their platform. In September 2020, Spotify announced a “virtual events” listing service but, ticketing is happening through a third-party platform (Songkick) and the streams are taking place on other platforms (Twitch, YouTube, etc.). In some ways, this is just the digital equivalent of Spotify’s previous “Concerts” feature where you could search for local concerts in your area and then purchase tickets through Ticketmaster, etc.

Since its earliest days, Spotify has throttled the intersection of music and social. They were one of the first companies to build on Facebook Connect and had a number of social features over the years that they’ve mostly killed off. Still, with collaborative playlists and Spotify’s viral end-of-year recaps, they are one of the most socially-conscious Western content companies.

An exciting next chapter for Spotify would be to build upon the social elements laid out by other platforms like Tencent Music to expand creators’ relationships with their users and open up new monetization paths.

Thanks for reading! 💜

If you enjoy this post or any other posts, please consider sharing, commenting, or just giving the post a “<3” on Substack

First published on October 26, 2020